This narrative is based on personal notes and written accounts, personal interviews and several newspaper articles about Henry Kane and his brother Richard. George Kane, Henry’s son, helped to facilitate the interviews conducted between February and June of 2008 at the Hudson Valley Health Care System Veterans Hospital at Castle Point, New York. Eileen M. Fontanella, of Hopewell Junction, NY, collaborated with the Kanes to write and complete the project.

In June 2008 the narrative was submitted to the Veterans History Project of the American Folklife Center at the U.S. Library of Congress.

This picture of Henry Kane was probably taken in 1941, while he was on leave to visit his folks in Little Britain, a rural area between Goshen and Newburgh, in New York state.

Introduction

Mr. Henry Kane served in the United States Military from October 1940 until June 1945. During World War II, in December 1942, he was captured in North Africa. For more than two years he remained a prisoner of war. During that time he was moved around to different camps in Italy and Germany. He escaped from Campo 59 (Servigliano, Italy) for a brief period, but he was recaptured a few months later and sent to other camps including Stalag 7A, 2B and a small work camp west of Stalag 1A in Germany (Koningsberg, Germany, known today as Kaliningrad, Russia). He was liberated by the 7th Armor Division.

Henry’s Story

Henry Kane was born on December 18, 1920, in Middletown, New York. He was brought up in Orange County, New York, where he lived and worked on various dairy and apple farms, including the Bull Farm on Sara Wells Trail in Hamptonburg. In the late 1930’s, when they were just teenagers, Henry and his brother Richard joined the Civilian Conservation Corp. Richard quit school at 16 in order to join, and soon after their brothers Walt, Durwood and James joined. Henry says that it was the only thing to do. Service in the Corps allowed the boys to save a little money to help their family and provided an opportunity to help their country. They each earned $30.00 a month, of which they were allowed to keep $8.00 in coupons for their use at the C.C.C. The remaining $22.00 had to be sent home. With five boys away at camp, the Kane family received approximately $110.00 a month. Camp life was highly structured, and the reserve officers in charge maintained the same discipline as military training. Henry worked eight hours a day at a camp in Peekskill, New York, until he was later transferred to Albany.

In October of 1940, Henry and Richard made their way to Whitehall Street, in New York City, to enlist in the U.S. Army. Although they were assigned to different platoons, Henry and Richard joined the 1st Infantry Division, 18th Infantry Regiment, 1st Battalion, Company A. The brothers began basic training in Fort Hamilton, Brooklyn, New York, in a unit dubbed “the subway soldiers.” After completion of basic training, Henry’s unit was sent to Fort Devens, Massachusetts. There, he engaged in combat training for mock beach invasions and other maneuvers (night marching, hiking distances in bad weather, etc.) Although Henry and Richard were the first of the seven Kane brothers to enter the military service, eventually all of the brothers, including Durwood, James, Walter, Harry and Joseph, would be a part of the United States Military.

This photo of Richard (left) and Henry Kane was taken in 1942 before they left for the United Kingdom. It was taken at the Kane family’s home on 192 Washington Street, Newburgh, New York. Several relatives came out that day to wish the brothers well on their journey.

Henry and Richard were in the Army for two years before they were sent overseas. They trained at many different sites along the Eastern seaboard from Massachusetts to Florida. They even participated in a show of maneuvers for British dignitaries during Winston Churchill’s visit. At one point Henry and Richard became interested in joining a paratrooper unit in Fort Benning, Georgia, but they abandoned that plan when their unit was sent to Fort Indiantown Gap Military Reservation, Pennsylvania.

Just as the war in Europe intensified, Henry’s unit received orders to ship overseas. On August 2, 1942, he and Richard departed Brooklyn, New York, on The Queen Mary (code name HMS 250), one of the fastest and largest luxury liners in the world. On August 7, after a five day transatlantic passage, the ship reached port in Gourock, Scotland, (Firth of Clyde). When they arrived in Scotland, the soldiers were surprised to learn of rumors that the Germans had sunk the Queen Mary at sea. Fortunately, these reports were inaccurate. Henry simply remembers that traveling on the Queen Mary was “wonderful.”

The men arrived at a naval base in Gourock and settled into tents and Quonset huts. Shortly after arriving they were transferred to Tidworth Barracks, Salisbury, England. By September 1942 they were in position for training—waiting and wondering what would happen next. They took a short R and R in Ireland and briefly visited London.

In October 1942 they received orders to ship out to sea under the code

name Operation Torch). A convoy of over 800 ships and 185,000 troops prepared to leave Glasgow Harbor and converge on North Africa at three different points. The 18th Infantry Regiment became part of the Center Task Force, made up of 37,000 troops and 104 ships.

This convoy of British and American ships approached North Africa in early November, 1942. Center Task Force, designated TRANSDIV 18 (Transport Division 18), had orders to land at Arzew, Mersa Bou Zedjar, les Andalouses and St. Leu, and then seize Oran and take Tunis. Henry and Richard headed to North Africa aboard the Ettrick (see photo), a British troop transport. The young brothers arrived at the same time, but they were separated during the invasion because they were in different platoons.

The battles were fierce and took their toll in terms of casualties and the loss of good men. The fighting in St. Cloud was intense and lasted for three days against the Vichy French. More daunting was the battle for Longstop Hill. Fighting continued at Longstop Hill on the way to Tunis. According to Henry, “We went into combat and never got out of it again. Our company was being sent up to the front line…We were sent as a suicide company. We didn’t really know what was there. We were told to go up a mountain and hold it as long as we could. We were told it would be against [German] snipers and machine guns. We went in knowing we wouldn’t come out, that we’d either be killed or captured. No one could help us.” (The Sentinel, December 18, 1986, p. 15.) He also remembers that when one of his buddies was shot, a devoted lieutenant held him in his arms until he died. The lieutenant was killed shortly after. Henry said that this is one time that he was “a little scared.”

On December 23, 1942, Henry’s company was taken captive near Longstop Hill, a mountainous region near Tunis. His memory of Longstop Hill is that of barren hills with little or no grass, trees or shrubs. He was captured by elements of the German 10th Panzer Division while walking in these stark hills. He said, “When you’re trapped like that…you’ve got to have the courage…” Henry’s recollection of this incident is that their captors walked them to Tunis, a distance just under 25 miles. Henry’s brother Richard was already in German custody when Henry and his fellow POWS came walking in the morning after the battle.

The brothers remember being treated reasonably well by their German captors, who were also front line troops. After a several days of interrogation, Henry and Richard were placed on an Italian destroyer bound for Palermo, Sicily. They were sent into the mountains near San Guiseppe, Jato, where they stayed for approximately one month. Henry believes that Italy was the most difficult place because their captors were so unpredictable in their distribution of punishment. The Italians sometimes threatened to shoot him, and he says, “I never knew if I was going to live or die.” The soldiers here were brutal; sometimes they hit the prisoners with blackjacks or guns for no reason. They forced the prisoners to bury the dead. Henry was forced to bury three soldiers. At one point an Italian guard hit him in the head with the butt of a gun.

Aside from the physical brutality, the living conditions were very harsh. The prisoners lived in tents and slept on slabs of wood with no blankets. While in camp, Henry met an American prisoner who spoke Italian and helped to interpret for him. He learned that some prisoners were stealing the wood from beds to burn as firewood and make tea. [This may have provoked the guards to punish the prisoners by hitting them.]

The men were eventually moved out of Sicily to the mainland. They were transported through Italy in boxcars (railroad freight cars). The trains stopped periodically to allow troop trains full of Germans to pass. This sometimes took many hours, which meant the prisoners were without food and water. Henry and his brother believe that the trains were stopped to allow the Italians to witness how many Americans had been captured. The men were hungry, dirty and cramped in the crowded boxcars. Their final destination, Campo 59, was to the north, near Servigliano, Italy. Henry and his brother arrived at this “Prisoner of War” camp around February of 1943. [Servigliano, a small town in the Marche area of Italy, is set inland from the Adriatic Sea, NE of Rome.]

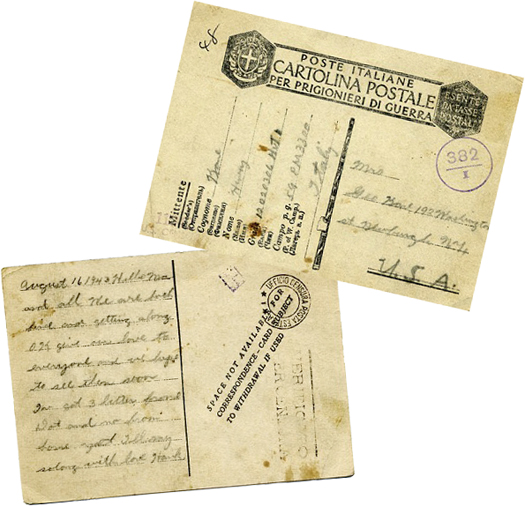

Life in Campo 59 was grim. Aside from constant hunger, the men were beset with bed bugs, lice, and horrible living conditions. It was cold and miserable. The men were sustained by watery soup as their one hot meal a day. They received Red Cross packages that helped them survive and gave them hope. In spite of their surroundings, Henry and Richard sent a postcard home to their mother that reflects their courage and indomitable spirit.

This postcard from Campo 59, dated August 16, 1943, reads:

“Hello Ma and all…We are both fine and getting along OK… give our love to everyone and we hope to see them soon I got 3 letters from Dot and no from home….I’ll say so long with love…Hank”

In the latter part of 1943, after about eight months in captivity, Henry and Richard made a bold escape through a break in the wall around Campo 59. According to Richard, “We took off about two or three in the morning some time in September…at the beginning we only walked at night; but after a while we even walked in the day time. We ran into one of our buddies from our company, and he joined us for the balance of our time in Italy. I had set our direction at southeast of the mountain and at least ten miles in from the Adriatic Sea…we did a beautiful job of staying on course. We walked almost half way through Italy [from Ancona to Pescaro] and came out right where we wanted to …of course, it wasn’t a smooth trip doing this…we ran into some road blocks along the way, like walking right into a German convoy that was parked along a highway…the Italians were trying to tell us to go back, that the Germans were there, but we couldn’t speak Italian, so we thought they were glad to see us…We got a big surprise! Needless to say we got out of there fast and laid low till night.” Henry’s recollection is that they walked by the stars, the North Star and the Big Dipper.

The brothers survived on figs and grapes as they made their way toward the coast. They would stop at a farm, forage for food and move on. They built make-shift shelters out of brush and moved every few days to cover their tracks. They encountered a few supportive families that allowed them protection and food. Some farmers let them pick grapes in exchange for food or shelter. Occasionally, an Italian family gave them bread, olives and wine. At one point they met some British commandos who gave them thousands of lira. In turn, the brothers gave the lira to the family that was hiding them. The two young soldiers were indeed grateful for the gifts of money, food, cigarettes or medical supplies, as they could not have survived without the help from villagers and sympathizers.

When the weather in the mountains became colder, they began to think about moving to warmer ground. Henry states, “We worked a few days and left to go south. Then, we walked during daylight after dying our uniforms blue.” Henry states it was important to dye the clothing so that they did not appear to have an association with the military. [Richard says that the uniforms were dyed dark blue or black by the Italians who sheltered them.]

Henry found that many of the Italians in the countryside were very kind to the American soldiers on the run. They fed them or sheltered them more readily than the people in the cities. At one point, the men met some lady friends who brought them food and wine. When the weather got colder, some of the women invited the fugitives to stay in their homes. One Sunday, in March 1944, just as the women were about to depart for church, one of them asked Henry and Richard to kiss a picture of a Saint. Richard states, “I am not sure here but I do know that as one of us bent over to kiss it, all hell broke loose…and I believe it was my brother that was about to kiss it… at this time they had one of the worst earthquakes (see photo) they have had in many years and I can say it was my first and I was scared. We could hear it coming…the house we were staying in split right in half…they had been keeping their grain up on the top floor and it all went to the bottom…they lost a lot…this was their food. We felt sorry for them, we tried to help them out as much as we could, but now it is time to move out…[It] was getting a little crowded there now… every one wanted to see their damage.”

As the brothers moved on, they witnessed the serious damage in the countryside and nearby towns. After they had followed the Appennines south for a while, they met a man who had lived in America for a few years. He invited them to stay with him, and they did for about six months. For a short time they worked near the city of Penne, helping out with the grape harvest and the making of wine. Henry remembers: “My buddy Christoff was on top of the hill and my buddy Masko was below the hill living in a house. My brother and I were in the middle house. We were there for six months.”

Henry and Richard became involved in meeting with some local partisans or “rebels” at this time. They thought they might be able to cross enemy lines to the front, but they never succeeded. Their involvement with the partisans eventually brought them to the attention of some German troops. Apparently some of these so-called “rebels” broke into a German commander’s home to retrieve some stolen goods [Italian fabrics and other personal items]. When the Germans started investigating, they stopped at the house where Richard and Henry had been hiding. When the Germans approached the owner of the house, the brothers escaped, but not for long. They were caught and interrogated. Their attempts to pass themselves off as Italians failed and they were taken to German headquarters in Pescaro.

The Germans brought the prisoners back to the shack where the guerillas had been meeting, searched the shack and set it on fire. The fire set off some of the hidden ammunition stashed there and further implicated the Americans. At this point, the brothers thought they were going to be killed, but the Germans brought them back to town and put them in a room with several German officers. They were told they would be sentenced, along with some of the people they had befriended and the man who had offered them shelter. According to Richard, “…the first man in line got the firing squad…he was sentenced to death.” One woman was freed, others were beaten and several were sentenced to a concentration camp.

Henry and Richard, along with the captured partisans, were taken to an area just outside of Rome. There they were put on a train and sent to a camp south of Florence [Camp 82 near Laterina near Arezzo]. Richard characterized this camp as “a hellhole.” If anyone was missing from the roll call, the Germans punctured the mattresses with bayonets to see if someone was hiding. After a short stay at this camp, the brothers were moved to Stalag 7A, a camp in Moosburg, Germany [near Munich]. They were marched ten miles to a train station, guarded by dogs and German soldiers who were ordered to kill anyone who attempted to escape. Their first trip to the station was futile, as the train did not appear. The men were marched back to camp, another ten miles, past the bodies of those who had been shot on the way to the station. Finally, the men embarked for Germany. However, their train was bombed while going through a tunnel north of Florence. Some of the prisoners aboard were killed, but the brothers were unscathed.

Henry’s account of the trip to Germany is peppered with statements that indicate the young soldiers and other prisoners were intimidated in many ways. He states: “They told us we were going to Germany and would have nice white sheets and live…They took us to get a train. They would shoot to kill us if we had to go to the bathroom. Many were killed and we stepped over dead bodies…”

Once at Moosburg, their work detail was assigned to repair railroad tracks. Henry witnessed many bombings, and he recalls leaving the train station near Munich one morning as bombers were approaching: “We were there to fix railroads. We got off the train. We could see bombers coming. The Germans didn’t tell us where the air raid shelters were. We were in a big underpass. Bombing all around us. There were 500 bombers going over every day carrying one-thousand pound bombs …” At this time the men were working up to ten hours a day repairing railroads. The stress of this work made them extremely nervous. “They sent a new bunch of POWs to replace us. We went back to camp and everyone was nervous.” They returned to Stalag 7A in Moosburg, outside of Munich, Germany. Henry remembers, “We had all kinds of nationality prisoners [including Russians, Brits and political].” This was a very large prison containing as many as 30,000 men.

After several months at Stalag 7A, the brothers were in transition again. This time they were headed far north but had a brief stay at Stalag 2B near Hammerstein, Poland.

A postcard written by Henry from Stalag 2B, dated October 8, 1944, reads:

“Hello Ma and Daddy and all …I hope this finds you all in the best of health. We are both fine and getting along OK. We hope to be home soon and we will be eating some of your cooking again. We’ll say so long with love…Dick and Henry.”

In late October 1944, the brothers were moved once again to a small work detail [of twelve] at the Polish border near the Baltic Sea. Henry and Dick remained together in this frigid land for several months. They cut two cords of wood a day. Henry said, “One cord for me and one cord for my brother with a cross saw.” His memories of this period capture the essence of terror these men endured: “We had to cook in a small area. We had a guard that was about 80 years old. The POWs got in an argument one night and the Germans hit me in the head with the butt of [a] rifle…We got American Red Cross parcels. We thought the cook was eating too much of our parcels. The guard said German headquarters gave orders to kill all GI prisoners… I thought it was the death march.”

During January 1945 the Germans started to move Allied prisoners [from East Prussia] to various cities: Gryfino, Berlin,Wolfsburg, Kassel, Hannover, Hamburg, Dusseldorf and Lubeck. Henry remembers: “We walked back and forth from January 1945 to May 1945. We would sleep in barns along the way at night. We were beaten on the legs and back when we didn’t walk fast enough. We would be sleeping and hear a plane overhead. One night the plane dropped a bomb. We got up [the] next morning…walked past a house. It was bombed.” Henry also notes, “Another worry… if someone lit a cigarette.” Clearly, he was concerned that their location would be identified by the light of a match.

Sometime in March or April 1945, the lengthy column of POWs, some 17,000 American, British, French and Italians, approached the Rhine River near Cologne. Henry states: “We were at the base of a bridge. We saw English spitfires. We watched them after they went fifteen miles or so in the air. They came back killing three German guards, fifteen POWs, and two of my buddies. That was a lot of stress. The British should have known we were POWs.”

From Cologne they marched toward Lubeck following the roads to Hannover and Hamburg. They were in a small village some 30 miles south of Lubeck when they saw armored tanks approaching. Henry suggested to Richard that they hide in a bomb crater until they could determine who was driving the tanks. They were glad to see the 7th Armored Division arrive, just a few days ahead of the infantry.

As victory emerged, the men were trucked to a nearby airport and then flown to Camp Lucky Strike near Le Havre, France. While in France Henry went to Paris, and by chance ran into an acquaintance from home, Henry Keller of Salisbury Mills. From France the brothers were shipped back to the USA and were processed at Fort Dix, New Jersey, for furloughs. They remained there until they were honorably discharged in September 1945. Henry and his brother returned home to Newburgh, New York, in June of 1945.

Since 1953, Henry has lived in Vails Gate with his wife Gertrude and children: George, Henry, Kevin, and, Karen. Henry became a bricklayerfor a few years with Local 5, but the work was seasonal and it was difficult to support a family and a home. In 1960, Henry was hired at West Point to do masonry work. He remained there for twenty-one years. When he left to become an independent masonry contractor, he worked for twenty years after that.

An End Note by Eileen M. Fontanella

Henry is a gracious and serene man. The warmth in his greeting is gratifying. He always smiles and treats you as if you are a long, lost friend. He has a wonderful sense of humor, and his repartee with his son is always delightful. When Henry, his son George and I spent one Sunday looking at his photos from the War, I could not help but notice that his facial expressions then, as now, reflect a positive, even cheerful demeanor. I asked Henry how he managed to return from war and imprisonment without any trace of resentment or bitterness. He smiled and said this about “bitterness”: “You can’t carry that with you…it will make you sick.”